By SWATI SAXENA

Learning from the recent starvation deaths in Jharkhand, the nation’s leaders must pay heed to the necessity of ensuring food security for all

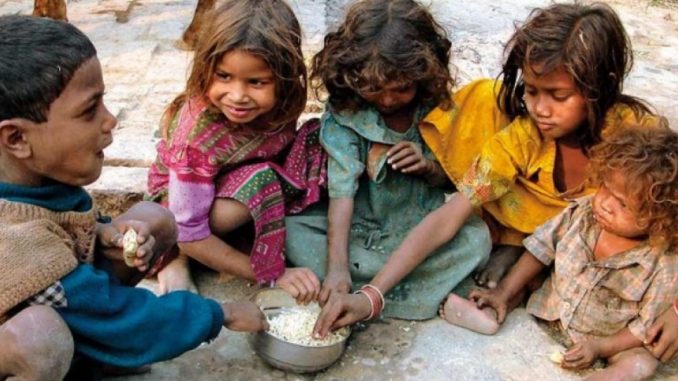

Food and hunger have been important issues this past month and the news has not been welcome. First it was India’s dismal rank in the Global Hunger Index (GHI) 2017 released by the International Policy Research Institute rankings — 100th among 119 countries. GHI looks at undernourishment, child mortality rate, child stunting and wasting to determine the status of nutrition, and India performs poorly on all fronts. India now comes under most African and Middle Eastern Nations and is one of the worst performing Asian nation, only a little above Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Next came the news of the tragic death of eleven-year-old Santoshi Kumari who died of starvation, asking for rice in her final words. The family was denied food rations from the Public Distribution System (PDS) as their Aadhaar was not linked to their ration card. This was followed by another death due to starvation in the same state. Baijnath Ravidas, a rickshaw puller, succumbed to long-term hunger as his family had neither ration card nor an Aadhaar number.

These deaths made the rankings and statistics palpable and tragic. Both cases demonstrated the failure of the system put in place to help people and brought out the cumbersome nature of the process. Linking Aadhaar to ration cards and then availing ration at PDS shops is a two-step procedure: first the cards are linked and then beneficiaries have to authenticate their biometrics at the PDS shops. However, people have complained that often the scanning machines and computers are non-functional or there is no Internet connection. Ravidas’s family also alleged that despite several applications and demonstration of eligibility, ration cards were not issued as middlemen were active.

Food or rather the lack of it, besides forming the crux of measuring poverty and development (India for the longest time defined poverty in terms of calories consumed) is also a political issue. Internationally, governments have been toppled and food riots have broken out when hunger reaches unacceptable levels in the society.

Historically, the Great Bengal Famine from 1942-44 gave impetus to the Indian freedom struggle that was to follow later. The issue of hunger underlay the great social revolutions of France and Russia. The commonly attributed phrase to Marie Antoinette (even though no such record exists) “Let them eat cake” in response to peasants having no bread to eat during famine in France became symbolic of the revolution. Food riots have also been common in the last few decades in the Middle East, for instance the 1977 Egyptian bread riots. The lack of food has been the result of various factors like climate change, failed economic policies, volatile food prices and resource scarcity, however, the lack has always manifested as colossal discontent with the government.

Likewise, India over the years has initiated a range of programmes to tackle food security. The National Food Security Act (NFSA), 2013 is perhaps the most significant and comprehensive legislation that aims to provide food security to over 800 million people through access to subsidised grains. It ties up with the Public Distribution System (PDS), a far reaching safety net for distribution with subsidised consumer prices for rice, sugar, kerosene oil and other commodities distributed through fair price shops. NFSA also subsumes Mid-Day Meal scheme aimed at giving free nutritious lunches to school-going children. Besides this NFSA makes special provision for vulnerable and needy groups like the poorest of the poor and pregnant women. Rural Indian women and children are also served by the Aanganwadis for health and nutrition-related issues.

However, the government circulars about linking Aadhaar to ration cards has created problems in accessing these schemes. Noted economist John Dreze recently stated in an interview that Aadhaar-based biometric authentication (ABBA) on the public distribution system in Jharkhand was not helping in removing the remaining irregularities and instead had created new problems leading to exclusion of more than 10 per cent of cardholders, especially the vulnerable. Moreover, the dealers were appropriating the leftover surplus denied to beneficiaries.

Given that deaths due to starvation are not just appalling on a moral level but can have serious political repercussions, governments have been quick to respond even if superficially. The Jharkhand government immediately cancelled circulars ordering the linking of Aadhaar with ration cards. Similarly, the state actors in power reacted to GHI, pointing to changes in methodology rather than addressing the issue which is that India continues to have one of the worst child malnutrition rates in the world and this severe problem of under-nutrition is also taking an economic toll on the nation.

A malnourished nation will make an unproductive workforce. Poor nutrition also impacts mental health along with physical health. Malnourished people, especially children, are more prone to infectious diseases. Children miss schools, workers miss work and the already burdened health infrastructure is strained. A country that is trying to project itself as an upcoming economic superpower cannot afford to neglect the health of its citizens.

Most importantly, malnutrition and hunger are not solely, even though primarily, dependent on the availability of food. Besides ensuring regular, affordable and acceptable food access, the state must maintain a multi-pronged strategy to maintain the health of the nation. This will include sanitation and clean water, better information about diets and accessible, free public health. There will also need to be a discussion around gender discrimination in food, cultural practices around how people eat and how the lack of access to food impacts the most vulnerable in the society.

Dr Swati Saxena is a researcher at a non-profit. She has a PhD in Public Health from University of London and a MPhil in Development Studies from the University of Oxford. The views expressed are her own.

Source: Tehelka (satire) (press release)

Leave a Reply