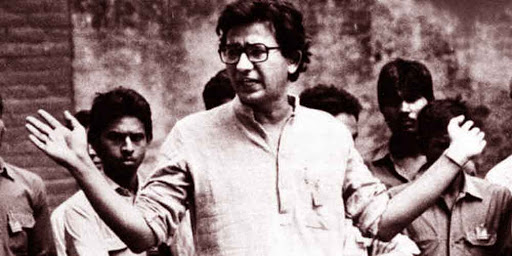

On the playwright’s 66th birth anniversary today

Sometimes death becomes more important than life. Think of Bhagat Singh. Or Che Guevara. Or Gauri Lankesh. We may or may not know in any real detail what they did in their lives, but we know how they died — or simply, that they died for upholding causes that they believed in. In their deaths, they acquire a stature that outgrows the achievements of their lives.

Something a little bit like this happened to Safdar Hashmi. It is over 30 years since Safdar Hashmi was killed while performing a street play in support of workers’ demands on the outskirts of Delhi. That attack took place on January 1, 1989. Safdar, severely wounded in the attack, died in hospital the following day. On the morning of January 3, about 15,000 artistes, intellectuals, political activists, workers and others took part in his funeral procession. Such a funeral procession for a theatre artiste has probably never taken place in Delhi. On January 4, less than 48 hours after his death, his co-actor, comrade, and wife, Moloyashree, led Jana Natya Manch to the site of the attack to complete the interrupted play.

It was a stirring performance, and captured the imagination of thousands of people all over the country. Safdar’s death became a catalyst for a massive movement in defence of the freedom of art and expression. Safdar’s birthday, April 12, was celebrated spontaneously as National Street Theatre Day by people all over the country. On that day in 1989, approximately 30,000 performances took place all over the country. Virtually every active street theatre group performed on that day; many groups which were dormant came to life; hundreds of new groups were formed. Safdar’s death had truly galvanised street theatre.

Who, then, was Safdar Hashmi, and what is his contribution to street theatre? Was he merely a romantic young man who became a hero because he was done to death at the young age of 34? Or was he merely a political activist who dabbled in street theatre?

In fact, Safdar was neither. He was romantic only to the extent that any revolutionary is romantic — recall Che’s famous statement, “The true revolutionary is guided by a great feeling of love. It is impossible to think of a genuine revolutionary lacking this quality.” And he was a political activist, a communist, because he genuinely believed that artistes have a social responsibility, and the logic of that responsibility led him to Marxism.

Jana Natya Manch (Janam), the theatre group that Safdar was a part of, was founded in 1973, after efforts to revive IPTA in Delhi proved abortive. Initially, Janam did large, open-air proscenium plays — these were plays by writers such as Utpal Dutt and Sarveshwar Dayal Saksena, and were mounted on makeshift platforms in front of thousands of people in urban working class areas and villages. Then the Emergency was declared in 1975, and Janam became inactive. Safdar was to regret this later on, and would often say that if such a situation arose again, Janam would find ways of fighting authoritarianism by performing — openly, if possible, clandestinely, if required.

When the Emergency was revoked in 1977, Janam regrouped, and started doing plays again. However, now the group found that the organisations which had hosted these plays in the past — trade unions, kisan sabha, etc. — were financially too weak to be able to afford these performances. Just the cost of putting up a stage in the open was too much. These organisations needed Janam’s theatre, but could not afford it. One way out of this could have been for Janam to perform in the established auditoria of the city, and somehow try and get their audiences to come to watch these plays.

Safdar, however, was clear: if the trade unions could not afford big plays, let us take small plays to them. Out of this impulse was born Janam’s street theatre. Today, when there is so much street theatre happening across the country, it is hard to imagine that none of the young men and women in Janam then had any idea what they were getting into. There simply were no established models of street theatre to look at and learn from. Whatever had to be done, had to be built from scratch. In fact, when they started reading existing short plays to consider for performance, they found none that suited their purpose. So they decided to write their own plays.

Safdar had not written a play before that. Nor had anyone else in the group. However, when workers at a factory called Herig India, demanding absolutely basic amenities, were fired upon, leading to six deaths, Safdar was certain that they had found their subject. He and another member of the group, Rakesh Saxena, collaboratively wrote a short play called Machine. Other members of the group contributed their ideas as well. The play became a huge hit with the audiences, who had seen nothing like this before. As Safdar recalled later:

“After we sang the final song, the trade union delegates . . . lifted us on their shoulders. We became heroes . . . The next day we performed at the Boat Club for about 1,60,000 workers. So you see, our street theatre began very gloriously… A lot of people tape-recorded the play… A month after the rally we started getting reports from all around the country that people were performing Machine… They had … reconstructed it in their own languages.”

One thousand shows later, Safdar still could not explain the success of Machine: “The workers absolutely love this play. I still do not understand (why), for it’s so simple … It is schematic, except that the dialogues are interesting. Everywhere they loved it, though … Perhaps it is something … abstract that appeals to them.” But Safdar has explained, here, the success of Machine: first, because of its stylised, lyrical, near-poetic prose; second, because it captures in its abstraction a very real, living truth and trusts its audiences to make the connection between the abstraction and reality; third, because abstraction and brevity lend it a certain simplicity, without rendering it simplistic.

What Machine did, then, was to encapsulate the basic framework of Janam’s street theatre has traversed to date: in the moment of its birth, street theatre allied itself with the people, the revolutionary classes in particular; it signalled the involvement of its audiences in the creative process itself (the idea for Machine came from a trade unionist); it placed poetry in the foreground; it laid stress on theatrical innovation; and it inspired several others to take up street theatre.

It is often assumed that street theatre and proscenium theatre are forms that stand in opposition to one another, that the former is “revolutionary”, while the latter is “bourgeois”. Nothing could be farther from the truth. Safdar himself was always clear that if Janam did nothing but street theatre between 1978 and 1988, it was only because the group did not have the resources to mount bigger plays. As he put it, “Theatre cannot be dependent on the frills and trappings which surround it. Drama is born with force and beauty in any empty space — whether square, rectangular, or circular. The play comes alive whether the spectators are on one or all sides, in darkness or in light.”

When he deemed that the time was right, he collaborated in writing a proscenium play with Habib Tanvir in 1988. This play was Moteram ka Satyagraha, based on a story by Munshi Premchand, and was directed by Tanvir. Prior to this, he had adapted Gorky’s Enemies in Hindustani, and he had ambitions of Janam producing the play at some stage. That was not to be. His script remained unperformed in his lifetime, and was produced by Habib Tanvir for the National School of Drama Repertory Company in the summer of 1989.

Safdar, then, was far from being sectarian in matters of art. He was forever willing to soak up influences from wherever he could, and was more than willing to try his hand at new forms and technologies. The entire area of video and television was just about opening up in the mid-1980s, and Safdar was quick to grasp its potential. He not only wrote and directed documentaries, he also scripted a full-length television serial on adult literacy and the empowerment of women, Khilti Kaliyan. He also wrote songs, poems and plays for children; he designed posters for a number of mass organisations; he took photographs; and he conducted theatre workshops. He worked for a while at the West Bengal Information Centre in Delhi, and was instrumental in organising the first Ritwik Ghatak retrospective in the Capital. He also organised screenings of Cuban films, in particular those of Tomas Alea. He was a major force in rallying artistes and intellectuals around issues of larger concern: at the time of the anti-Sikh riots in 1984 and subsequently in defence of secularism; in reviving the legacy of Premchand; in rallying artistes and intellectuals in support of the seven-day strike in 1988.

Habib Tanvir later recalled: “Safdar was an extremely broad-minded man, in a political sense. He wanted to open a broad cultural front. He could write poetry and plays, paint, act and sing. His idea of a cultural front was not confined to theatre. He visualised painters, musicians, singers, dancers, writers and critics — all to be drawn into a movement out of common interest . . . (He was) a creative genius, endorsed with the zeal, energy and determination of a far-sighted organiser and theatre visionary.”

Safdar became a communist because he was fired by revolutionary ideas. Three decades after it was brutally snuffed out, that luminous, red-hot life continues to inspire. Today, on campuses across the country, as well as at protest sites such as Shaheen Bagh, you can see Safdar Hashmi’s portraits, or lines from his songs and poems. Safdar is alive. In people’s struggles.

Source: The Tribune

Leave a Reply