By Rohan Abraham

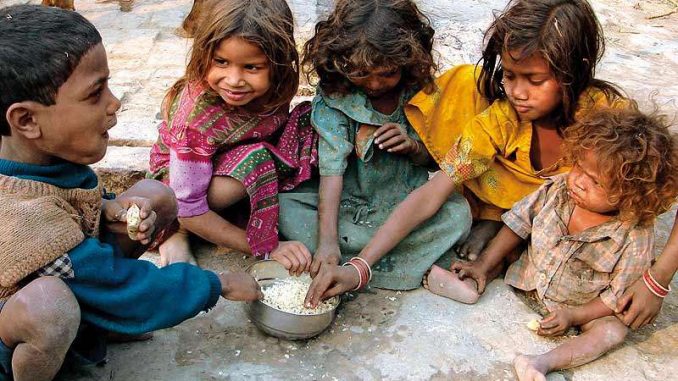

While food production is still not insulated from the vagaries of nature – which can vacillate between extremes – ranging from the floods which ravaged parts of Northern India this year, to the extant drought in the South, anthropogenic factors are holding back India’s quest to attain food security.

On the occasion of World Food Day, which is celebrated on October 16 to commemorate the founding of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), it is fair to say that a Malthusian prophecy has been averted, but catastrophe of another kind looms large. Thomas Malthus’ prediction that an exponential growth in population would outpace agricultural production, has to an extent, been contained, but migration, war, natural calamities have contributed to rendering scores of people, especially in strife-torn areas without access to food.

The theme for this year is “Change the future of migration. Invest in food security and rural development.” According to a report published by the International Food Policy Research Institute, India ranks 100 out of 119 countries on the Global Hunger Index. It is outperformed by countries in the neighborhood such as China,Nepal,and Myanmar, which are ranked 29, 72, and 77 respectively.

The methodology used to prepare the index takes into account malnutrition, stunting among children, wasting, and the mortality rate of children under the age of five. By assigning weights to these variables and standardizing the component indicators, the index value is calculated, and subsequently sorted to arrive at the overall rankings.

Here are some of the reasons exploring what ails India’s quest to attain food security.

Crop cover is getting denuded

According to a reply furnished by Radha Mohan Singh, Minister of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare, in the Lok Sabha on 2nd August, 2016, the average area under cultivation has been steadily on the decline. Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare data reveals that 12.25 lakh hectares of land which was under cultivation in 2006/07, has been diverted for non-agricultural use. Rajasthan leads the pack with 2.55 crore hectares under cultivation, an area roughly four times the size of Sri Lanka.

Food imports touch ₹1.4 lakh crore

As per Census data, 176 million, or 56.6% of India’s working population are engaged in agriculture or allied industries. Despite an overabundance of farm hands, India’s food bill has seen an unprecedented spike from ₹56,196 crore in 2010-11 to ₹1,40,268 crore in 2015-16, marking an increase of 149.6%.

Given the fragile nature of foreign exchange, an import bill of this enormity, is a setback in the government’s efforts to reducing the fiscal deficit. However, in relative terms, India’s food import bill accounts for only 5.63% of total national imports in 2015-16.

Agricultural productivity is declining

Despite having large tracts of land under cultivation, Rajasthan doesn’t stack up with other states in terms of agricultural productivity. According to the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation’s Statistical Yearbook on Agriculture – 2016, the net yield for Rajasthan was 1,535 kg/hectare. Punjab and Haryana were on top with 4,144 kgs/hectare and 3,772 kgs/hectare respectively.

The national average of 2,070 kgs/hectare is well below the productivity levels of the farm sector in developed countries such as the United States of America and the United Kingdom, which enjoy yields of 7,638 kg/hectare and 7,697 kg/hectare respectively, according to data compiled by the World Bank, in association with FAO in 2014.

The bumper yields of farmers in the Middle East present a point of contradiction, since the topography and weather of the region pose hurdles in optimizing agricultural produce. Agricultural productivity in the United Arab Emirates was 41,908 kg/hectare, while that in Kuwait was 21,845 kg/hectare.

Land holdings are shrinking

The average size of operational holdings has come down to 1.15 hectares in 2010-11, from 1.33 hectares in 2000-01, Agriculture Ministry data shows. As profit margins blur into operating losses, small farmers end up in a debt trap, since the cost of cultivation often overshadows the market price of their yield. Despite migration to urban centres, hidden unemployment is also rampant in the agriculture sector.

Commercial farming has increased agricultural productivity in parts of the developed world. According to data compiled by the FAO, the average area per holding in North America is 117.8 hectares, while the global average is 5.5 hectares.

Source: The Hindu

Leave a Reply