India, one of the world’s largest consumers and importers of pulses, may soon take over agricultural land in Africa and Myanmar to meet growing demand in its domestic market.

Two consecutive years of drought have led to a sharp drop in pulse production in the country. As a result, some pulses have been selling atRs200 a kilogram in the past few months—up by over 30%. Rising food prices, in turn, have fuelled retail inflation. In May, consumer price inflation rose to 5.76%, the highest in 21 months.

To plug the demand-supply gap, the government is exploring opportunities to import and take up contract-farming with countries such as Mozambique, Malawi, and Myanmar. “We may cultivate pulses there or sign a long-term agreement (to procure). For this, we are sending a team to Mozambique and another to Myanmar,” India’s food minister Ram Vilas Paswan told NDTV earlier this week.

On June 21, a delegation led by Hem Pande, secretary of consumer affairs, was also despatched to Mozambique. “The delegation will explore both short-term and long-term measures to import pulses from Mozambique on a government-to-government basis,” the consumer affairs ministry said in a statement.

Supply glitches

Meanwhile, the Narendra Modi government is taking other steps to deal with such shortages.

A high-level meeting chaired by finance minister Arun Jaitley on June 15 decided that India will import a volume equal to the gap between the demand and supply of pulses. Next day, the government ordered imports of some 0.65 million tonnes from Myanmar and other African nations.

Until now, traders have also resorted to importing these pulses, but it hasn’t solved the problem. For instance, so far in 2016, private traders have imported three million tonnes of pulses, compared to the 5.79 million tonnes imported in entire 2015, according to the Indian Pulses and Grains Association.

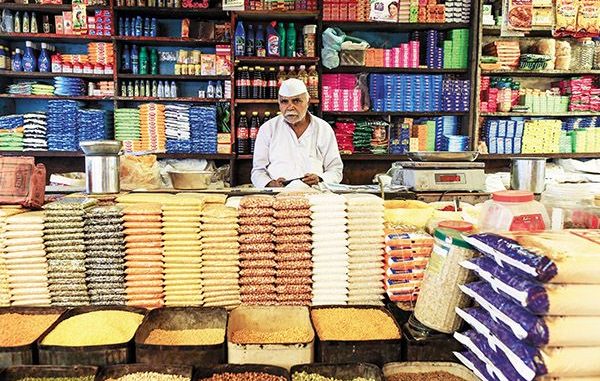

India is estimated to have produced 18.32 million tonnes of pulses (pdf) in the crop year, which ran from July 2015 to June 2016. Demand, meanwhile, stood at nearly 24 million tonnes. Pulses in India typically are tur, gram, moong, and urad, among others. They form a substantial part of the Indian diet.

“Over time, supply of pulses has failed to catch up with demand. Production remained stagnant for nearly seven years since fiscal 2004, while demand accelerated, causing per capita availability of pulses to decline and prices to spiral,” Dharmakirti Joshi, chief economist at Crisil, a ratings agency, told the Hindustan Times.

Contract farming

India, of course, isn’t the only country to use agricultural land overseas to grow crops.

China is currently cultivating crops in Mozambique and other African countries, but it hasn’t been a smooth operation. Earlier attempts by India’s private sector, too, haven’t quite succeeded.

In 2009, for instance, eight Indian firms had formed a consortium to purchase or lease land in Uruguay in South America, and grow pulses and soya bean. The global slowdown, however, made these investments unviable and the plans never materialised.

“Stability of governments and financial viability are factors which make Indian business think 10 times before buying land in African nations,” B V Mehta, executive director of the Solvent Extractors Association of India, part of the 2009 consortium, told the Business Standard newspaper.

This time around, though, the demand for pulses is pressing and the government will have to find a way to make its plans work.

Leave a Reply