Minus Satkosia no one can write the history of Gharial Crocodile Conservation of India: Dr. Lala A.K. Singh

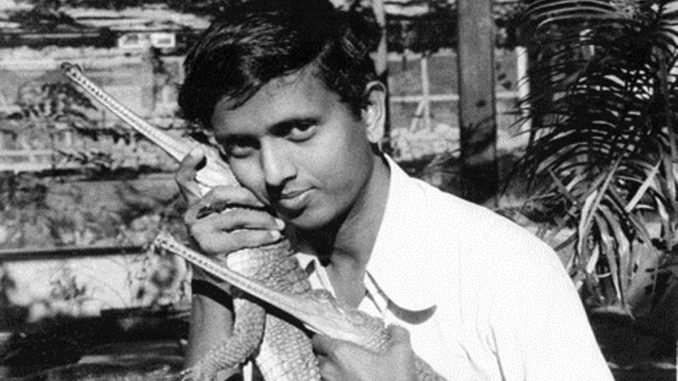

Dr Lala Ashwin Kumar Singh an eminent Wildlife Researcher and Member- IUCN Conservation Breeding Specialists Group popularly known as the father of crocodile research projects and conservation of India. He is the founder member of Rastriya Chambal Gharial Project and Research Gharial work at GRACU.

Dr. Singh spoke at length to Bibhuti Pati about Satkosia being a wonder land which saw the failure and success of crocodile conservation in India and then how Satkosia captured the imagination of the world about Gharial conservation.

Why crocodile conservation is important?

In 1970s, the answer for us as Indians, was biased for their commercial potential and the possibility for earning foreign exchange; but over the years we learnt more about their ecological, academic and diplomatic roles, and the legal protection given to them as Schedule-I animals of Wildlife Act, 1972.

In aquatic habitat, crocodile is the topmost carnivore. As an indicator species, it is able to regulate the population of other aquatic biodiversity; it is the major predator of predatory fish, so they enhance the chances for survival and growth of most other fishes; it is also an effective scavenger for dead animals, — the ancient tradition of leaving afloat the dead bodies in Ganga or other rivers is an example; even the gharial (Gavialis gangeticus) is able to perform the role of a scavenger within the limitations of its narrow long snout.

We are happy that, starting in 1975, in just next five to six years the crocodile conservation project became a thumping success as a multidimensional national wildlife project for conservation, research, training, international collaboration and the launching pad for conservation of marine turtles and mangroves, among others significances. Some of the areas notified as crocodile sanctuaries have subsequently expanded as Tiger Reserves in Andhra Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Odisha, or have overlapping territories of elephant reserves. Water is the main life support system and crocodile waters are rich wetlands of biodiversity. In fact, the first three wildlife sanctuaries of Odisha Bhitarkanika, Satkoshia, and Hadgarh were started as notified crocodile sanctuaries. The knowledge and inspiration from Satkoshia led to the start of Central Crocodile Breeding and Management Training Institute (CCBMTI) at Hyderabad in 1978.

How did you, as Lala Aswini Kumar, get interested in crocodile conservation? Was it out of interest or an opportunity?

Even in my time one always looked for opportunity, and interest had to be accommodated within that in finer aspects. I had not seen Satkoshia before joining as a Research Scholar. We read about Satkoshia in our school text books.

Some surrounding experiences in childhood had their impact and orientation; they nurtured a better student of me in Zoology. I have noticed the presence of darters, shags, king fishers and dragon flies, while walking on mud over earth-worm soil-exudates and snail trails, along the shores of the Majena-pond of Lord Jagannath behind our house. With peers I admired the Brahminy kites, chased away the Pariah kite, and followed steps of the elephants of Puri Gajapati Maharaja as they walked on the road in front of our house. Then, Puri sea coast had offered me to build small temples with sand and pebbles, and count crabs, stranded fish and the dead molluscan shells.

During postgraduation in Zoology at Utkal University, my 1974-MSc project produced five research publications relating to Aphis insects. It set an academic trend, and enabled me to stand prominent as a research student.

After MSc in 1974, Prof B. K Behura was weighing my interest on possible topics for a PhD dissertation, when Dr H. R. Bustard- the FAO Crocodile Expert and Sri Rangadhar Mishra- the Wildlife Conservation Officer of Odisha Forest Department one day visited the PG Department of Zoology. They talked about the upcoming project on crocodile conservation and the need to have research scholars.

Successful conservation goes hand in hand with research. So, government processes had started. I was one of the 35 candidates to undergo a series of tests in the campus and in Satkoshia, and I am one of the two finally selected, and I started on gharial at GRACU (Gharial Research and Conservation Unit), Tikarpada-Satkoshia-Mahanadi. Odisha is the first Indian state to start with full-time wildlife research scholars.

As a matter of coincidence, my maternal grandfather had left chilling narrations in the family, as he was from Angul, served at Purunakote in the police before independence, was using pigeons for communication, and moving by horse through Tikarpada and the adjoining forests. Today I feel, God had identified me in His list of people to work for His animals who cannot speak and complain.

How has been the national road map for gharial conservation to and from Odisha?

In 1971, Government of India thought of starting commercial crocodile farm in Delhi Zoo and sought financial assistance from UNDP. In 1974, FAO Expert Dr Bustard conducted an all-India survey and in his preliminary report on the prospects, of the three Indian crocodilians, Gharial was facing imminent extinction, muggers were depleting faster than they could reproduce, and the saltwater crocodile along with its mangrove habitat was endangered. The national project took a start from Odisha the state is having all the three species in their natural habitats, and the gharial project was launched at Tikarpada because of the Satkoshia as potential gharial sanctuary, remoteness of the site people could directly participate in every stage of the project.

The project was launched on the principle of “Grow and Release Technique”, to reduce natural losses to eggs, mortality of hatchlings and growth up to three to four feet size for restocking wild areas. This is the size when crocodiles have enemies among men and other crocodiles.

Information from Katerniyaghat along river Girwa in Uttar Pradesh bordering Nepal, and from different parts of Chambal in Rajasthan, UP and Madhya Pradesh were coming forth to help the expert, stationed at Tikarpada, plan gharial conservation strategies better. A collaborative gharial survey by New York Zoological Society and Madras Snake Park, with the help of surveyor (late) Dhrubaraj Basu of UP was complete.

Mr. Sushanta Choudhury and Mr. Ajai Srivastava of Lucknow also worked for important information and contributions for academic goals. The contributions by Sri VB Singh, CCF-UP and Sri JJ Dutta CCF-MP were of high significance. Similarly, the contributions from Mr Pushp Kumar, then Director of Nehru Zoological Park, Hyderabad was very inspiring in setting up the first institute of Government of India directly under the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperation, which handled the forest and wildlife affairs in those days.

The Central Crocodile Breeding and Management Training Institute (CCBMTI) which came up in Hyderabad as a part of the UNDP/FAO project, grew to an international institute for training in-service people from forest and wildlife departments, covering the subjects of wildlife sanctuary and crocodile management. Later, in 1987-87 it contributed and merged with the wildlife division of Forest Research Institute, for initiating the Wildlife Institute of India, Dehra Dun.

By the time the UNDP/FAO project ended in 1982, we were having at least 34 crocodile rearing stations and 34 wetlands where crocodiles were found or rehabilitated. It has been a combined effort of at least nine states in the country. Captive breeding of gharial could be achieved first at Nandankanan Biological Park, Odisha

In 1975 itself, when the expert saw more of Satkoshia, the geographic contour and hydrological profile of Satkoshia was considered an ideal model for gharial breeding and was used for designing captive breeding facility at Nandankanan. There was no male gharial in captivity anywhere in India. The Frankfurt Zoo, Germany donated a male Gharial, that was air-shifted to Bhubaneswar-Nandankanan.

Why is Satakoshia a perfect place for Gharials?

Gharials have always been present, though under various threat in parts of Mahanadi other than Satkoshia. Satkoshia was known to the Forest Department as a crocodile stretch. We didn’t have enough interaction or knowledge about other places in Mahanadi or Odisha. After the project started, Dr Bustard and I had boated along Mahanadi from Larasara downstream to Satkoshia, covering 10-12km every day. Mr Bisweshwar Mishra rendered all support as the Conservator of Forests of Sambalpur. Later, in 1976 I surveyed the Mahanadi upstream Hirakud and downstream through Satkoshia to the delta. In the process, although we knew about the presence of gharials outside the Satkoshia Sanctuary, around Boudh and upstream tributaries, but the focus of the project was on Satkoshia as Sanctuary from 1976, and the objective to achieve the best and quick success under “grow and release technique’.

Within Satkoshia, gharials were visible and monitored from close distances; they were breeding; laying eggs in 1975-77; and we studied their movement and parental care. The ideal situations were deep flowing, perennial pools; tributaries and streams as monsoon retreats; high sandy slopes for nesting as well as flat sand banks for whole-day basking by gharials of different size classes; and for food, there were plenty of fish from fingerlings to the large ones.

What remained to be done were to stop, regulate and manage the adverse human dimensions related to nylon set-nets for fishing since 1950s, fishing camps that used to be set on flat sand banks by fishermen visiting from other parts of Mahanadi and adjoining districts (local fishermen come from their houses, set fishing floats, collect their catch and return in the evening, harmlessly for gharials), the entire range of operations leading to bamboo rafting along the Mahanadi for supply of raw bamboo from forests to the paper mill at Chowdwar near Cuttack, and the operation of a heavy-duty motor boat by CPWC for collection of data on changing water level.

At GRACU I had fixed bamboo poles from summer level datum and measuring the changes for correlating gharial behaviour. Also, there was a rain-gauge and Stevenson’s screen at the meteorological station for 24-hour record of max-min temperature and relative humidity using a thermo-hygrograph. Research orientation and such simple equipment seem to have gone abandoned.

Did the technical and administrative circle ever sense any threat over the success of gharial conservation in Satkoshia?

Gharial conservation was a new subject for all of us. As a species unique to the Indian subcontinent, it was also new for the FAO Expert, but he had a great sense of understanding of the crocodilian ways of life, which he taught us and inculcated into the project. Several possible threats in Satkoshia were gradually understood and recognised when we thought like gharials, the breeding parents.

Producing a large number of gharials was in our hands; we were fast developing the skill and were good at it. Rest of the things were on managing human dimensions, which continued to remain with us in spite of having founding officers like Mr Bhagaban Kanungo- Conservator of Forests and Mr Nityaranjan Bohidar- DFO-Angul.

Gharials of Satkoshia were given protection under old provisions when the Conservator of Forests had the power to declare a sanctuary. The Satkoshia Gorge had territories under Revenue Department Collectors of Phulbani, Puri, Angul and Cuttack. The Divisional Forest Officer of Angul had ensured deployment of local people on boat for monitoring and protection of gharials in the Gorge.

What exactly were the obstacles for you in the first phase at Tikarpada, GRACU?

Obstacles were the lack of knowledge about gharial as a species in biology and as a species in management. We didn’t know its ecological and biological requirements that we learnt gradually and have shared with the world. The first ever gharial PhD dissertation was produced from GRACU in 1978. As Dr Bustard would say, I was working with facilities that was one third of a British student and a tenth of an American student. I didn’t have a calculator for three years; there was no type writer, no electricity, no drinking water, and so on.

By the end of 1978, we were having crocodile research scholars posted in Tikarpada, Bhitarkanika, Hyderabad, Nandankanan, Lucknow and Katerniyaghat. There were some good field surveyors, as well. So, at Katerniyaghat the CCBMTI organised a symposium of the scholars to pull in the status of knowledge and develop recommendations for future. It is still a very valuable document; I have uploaded in the net along with others from my publications.

Satkoshia has taken a back sit in Gharial Conservation, when compared to National Chambal Sanctuary! How do you see that?

See, in the contemporary world, all species cannot be conserved in all their former ranges. The problems in species conservation, although similar in certain aspects, are unique in their quality and magnitude for each indicator species and each geographical entity of management. If we extend our attention outside Satkoshia along Mahanadi, as per some of my recommendations in the 1991-analysis on non-survival, we may see more of gharial returns to Satkoshia. Satkoshia is the smallest best stretch along Mahanadi, but potential breeding sites existed at several places along the river between Larasara and Satkoshia through Bada Nadi, Tel Nadi, Boudh-Shyamsundarpur and the island of Morjakud. Let there be conservation reserve or community reserve to help revival of gharial and aquatic life beyond Satkoshia, with the help of people. Compared to 570km long Chambal, Satkoshia is only sat kosh, or fourteen miles, 22.4km- that’s all.

How do you present gharial in the context of common crocodilian notion about their behaviour relating human-predation and cannibalism?

As we know, gharial is a specialised fish-eater. Its snout is designed for eating fish. But it can also be an effective scavenger when opportunity exists. In long past, gharials were blamed of predating up on humans because ornaments have been recovered from some dead gharials. As I have said always, a gharial may acquire such ornaments from dead bodies swept into or left afloat in rivers as a token of belief and rite. I know of cases from Naraj and Tasera along Mahanadi where gharials have accidentally caught the fishermen but immediately released them from the jaws, and they alive with jaw marks.

As regards cannibalism, I never contribute to such suggestions. Gharial female and male is very good mother and father. Their display of affection for survival of their progeny starts with their return after flood to a breeding zone where they have good water and good nesting sites. The performs trial nests, and then digs actual nest. She remains in water and guards the nest from water. When the hatchlings are ready to hatch, the mothers digs them out and leads them or carry them in mouth to water. Diligent and dominant mothers bring hatchlings from adjacent nests to their crèche and jointly guarded by the male and female parents in their hierarchal order. As the flood approaches and water level rises, the mother guides the hatchlings to tributaries and side streams.

Tell us about the Chambal Field Research Camp, that you started and are still analysing field data that have piled up over the last three and a half decades.

After 1982, when the UNDP/FAO project ended, at the behest of Government of India, I had started a field camp in the Deori village gharial rearing unit of Morena district, Madhya Pradesh. My initial target was to fit radio-transmitter to gharial and study their movement back in nature. But within one year I found running around ten different study objectives. Our sustained work in National Chambal Sanctuary from 1983 onwards has highlighted the ecological associates of gharial like the Gangetic dolphin, the mugger crocodiles, the otters, the freshwater turtles, the migrating wetland cranes, storks and ducks, and the raptors coming from adjoining forest-based sanctuaries of Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh, and so on.

A scientist never retires. After superannuation from responsibilities with the Government, I got more time to attend to volumes of unanalysed data with Dr RK Sharma. For Chambal I wish to see revival of a team like the one I had with Dr RJ Rao who is now in Jiwaji University in 1980s and Dr RK Sharma who retired from NCS in 2016.

Dr Jeff Lang from University of Minnesota-USA and his Turtle Alliance group from UP are doing wonderful work in Chambal and Yamuna. Similarly, gharial rehabilitation work in Beas in Punjab is a very welcome experiment to see their revival possibilities. Jharkhand has kept a gharial conservation spirit live in Ranchi. The PhD work by Dr Ainul Hussain from Chambal in 1990, the work by Mr BC Choudhury and his students in Gandak for gharials in recent years, Dr Raju Vyas and his team in Gujarat for mugger crocodiles, and the very long years of work (from 1975 till now) by Dr Sudhakar Kar on porosus and mangroves in Bhitarkanika have kept the crocodile temperaments live.

What more do you want should be done for the gharials?

Dream is limitless, and Gharial is just a means or medium. Our actions have always been oriented towards the entire aquatic ecosystem, for all species of crocodilians, wildlife and biodiversity. The project has extended services and planning for marine turtles in Odisha coast, the mangroves in crocodile habitats of Odisha and West Bengal Sundarbans.

I wish there should be long-term monitoring in all gharial habitats, all porosus (estuarine crocodile) habitats and selected mugger habitats in the country. We will know a lot about these wetland diversities. There should be the revival of an institutional mechanism to coordinate the crocodilian activities in the country. The mechanism can be broad based to cover the wetlands in freshwater, estuaries and the coast with turtles. It should give academic and knowledge support to all. For example, crocodile managers should think the requirements of crocodiles like a crocodile mother.

After a long waiting of 46 years, The Glory reached but after 46 days it has faded away. This life; Ephemeral! Do you think this is very much appropriate for 28 missing baby Gharials of Satkoshia?

The discovery of 28 hatchlings was possible because, it was nesting elsewhere in Mahanadi and returned to Satkoshia for nesting. The staffs were vigilant in Satkoshia, there were strict fishing regulations for some years and the calmness is brought by Covid-lock-down. The hatchlings were not from a maiden clutch. The maiden clutch of gharial may consist of just six eggs without hatching, and 12 eggs with 75% hatching. A crèche of 28 hatchlings means, even if 100% hatching occurred, it is the 3rdyear or 4th year or older instance of breeding by the mother. Obviously, the female was breeding outside the Satkoshia sanctuary, and remained unnoticed.

Regarding the disappearance of mother and hatchlings, it is to be understood from the mother’s angle. There must have been certain disturbances because of motor boat movement, or people visiting there, or the movement of drone for monitoring. It appears, the mother didn’t accept some such happenings as safe to keep the crèche of hatchlings. So, she has shifted to some other area. They have shifted but reason is back to human-origin, absence of training to crocodile managers to think like crocodile parents! CCBMTI of Govt of India doesn’t exist and no institutions to teach about the art and science of crocodile conservation. This will say that crocodile work is going on without training and knowledge

What was your best single experience overseas, while working for crocodiles?

Because of crocodiles I could touch six of the seven continents, had studies in the USA and Zimbabwe, and represented the country in Australia and Venezuela. As regards my best experience, difficult to single out, but I would say about the standing ovation given to me as the Leader of the team and my two colleagues Sudhakar and Binod, in Caracas by over 300 participating members of the IUCN/SSC Crocodile Specialists Group 1984-meeting, when the Chairman Professor Harry Messel gave a call to applause the success story of Indian crocodile conservation in the hands of the young biologists. I still feel very nostalgic about the experience.

Leave a Reply