By Colin Gonsalves

India has undermined its prestige by repeatedly promising — and failing — to ratify the Convention Against Torture

The Convention Against Torture (CAT) came into force in 1987 and India signed it in 1997. Today, the CAT has 162 state parties; 83 are signatories. In refusing to ratify the CAT, India is in the inglorious company of Angola, the Bahamas, Brunei, Gambia, Haiti, Palau, and Sudan. In 2008, at the universal periodical review by the Human Rights Council (HRC) of the UN, country after country recommended that India expedite ratification. India’s response was that ratification was “being processed”.

Promises to keep

In 2011, desiring to be appointed on the HRC of the UN, India took the extraordinary step of voluntarily “pledging” to ratify the CAT. The pledge stated: “India has been a consistent supporter of the UN human rights system” and “remains committed to ratifying the CAT”. Once on the Council, India forgot its commitment. In the 2012 review, once again countries overwhelmingly recommended that India “promptly” ratify the CAT to which India responded “supported”, which indicates agreement. The review said: “India’s NHRC had reported a significant number of torture cases involving police and security organisations.” The concluding recommendation of the Working Group was that India ought to expeditiously ratify the CAT and enact a Prevention Against Torture Act. Again this year, at the universal periodical review, India reiterated “its commitment to ratify the CAT”. India has been making promises but doesn’t seem intent on keeping them, much to the dismay of the countries attending the review proceedings.

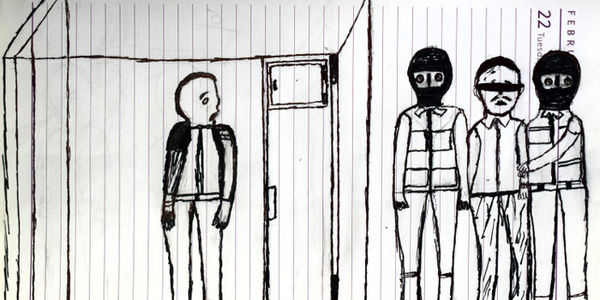

Meanwhile, torture cases have escalated in India. In Raghbir Singh v. State of Haryana (1980), the Supreme Court said it was “deeply disturbed by the diabolical recurrence of police torture.” “Police lock-ups,” it said, “are becoming more awesome cells.” In Shakila Abdul Gafar Khan v. Vasant Raghunath Dhoble (2003), the Supreme Court said that “torture is assuming alarming proportions… on account of the devilish devices adopted. The concern which was shown in Raghubir’s case has fallen on deaf ears”. In Munshi Singh Gautam v. State of M.P. (2004), the Supreme Court said: “Civilisation itself would risk the consequence of heading towards total decay resulting in anarchy and authoritarianism reminiscent of barbarism.”

In response to India’s pathetic excuse that it was necessary for Parliament to enact anti-torture legislation prior to ratification, a fitting answer was given by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, who said that it was “an erroneous idea” and “a misconception” that the state must enact legislation first and ratify later. Ratification only signals the beginning of a process to amend national laws so that they conform to international human rights standards. It demonstrates goodwill and political intention to comply with international norms and standards.

A step forward

The Prevention of Torture Bill, 2010 was an excellent attempt by Parliament to draft new legislation. Unlike Indian law, which focusses on murder and broken bones (grievous hurt), torture was expanded to include food deprivation, forcible feeding, sleep deprivation, sound bombardment, electric shocks, cigarette burning, and other forms. The Indian police force uses these techniques. In the same year, a Select Committee of Parliament endorsed the Bill and made some positive recommendations for rehabilitation, compensation and witness protection. The Select Committee noted that an overwhelming number of States and Union Territories were in favour of the Bill. The Bill was allowed to lapse.

A petition was then filed in the Supreme Court in 2016, seeking a direction to the Union government to ratify the CAT. Despite its numerous promises to the UN bodies, the government opposed the petition saying that the Law Commission of India was considering the issue. This excuse was also rendered useless by the prompt production of a report by the Law Commission strongly recommending ratification and the drafting of comprehensive legislation instead of ad hoc amendments in the Indian Penal Code. The Centre remains adamant to not ratify as it is deeply apprehensive of transparency and the involvement of the comity of nations in the post-ratification processes.

In showing the world that India has no intention of combating the terror of its own forces and of implementing its promises made to the UN, the government has undermined India’s prestige. To be a world power, India must act like one.

Colin Gonsalves is founder, Human Rights Law Network, and Senior Advocate at the Supreme Court

Source: The Hindu

Leave a Reply