By Karishma Mehrotra

The research shows that India’s mobile phone gender gap – 33 per cent – is among the highest in the world, surpassing several countries with comparable incomes, development levels, and mobile phone costs.

Apart from economic constraints, social barriers like the level of education, marital status and the lack of empowerment prevent women’s access to mobile technology in India, suggests a study by the Harvard Kennedy School.

The research shows that India’s mobile phone gender gap – 33 per cent – is among the highest in the world, surpassing several countries with comparable incomes, development levels, and mobile phone costs. The numbers vary: while this study found a 12 per cent gap in mobile access, LirneAsia reports 57 per cent gap in Internet usage.

The study, by Harvard’s Evidence for Policy Design (EpoD), combined quantitative data from two sources: Financial Inclusion Insights (45,540 respondents in 2016) and India Human Development Survey (26,607 ever-married women in households that own a mobile in 33 states in 2012) and combined it with interviews in five states to understand the dynamics for this study.

The Harvard Kennedy School study is among the first to focus on the reasons behind the gender gap in India.

Marital status has little impact on the gap, except when combined with age. For single women, the gap starts at above 30 per cent at ages 15 to 22 and steadily reduces with age. For married women, the gap of above 30 per cent at ages 15 to 22 does not change as significantly with age. While the gap in urban areas did not change much with age, the gap in rural areas surged, peaking in the 23 to 30 age group at almost 40 per cent and dipping in the above 40 group to a little over 30 per cent.

In addition to the data analysis, the researchers’ interviews found widespread beliefs that mobile phones are a risk to a women’s reputation, that married women have a primary domestic responsibility, and that women fear online harassment.

In some interviews, female phone ownership and usage were associated with promiscuity, and in one case, a local community organisation had instituted a fine for families that allowed unmarried daughters to own phones. Women in one focus group stated that their families also demanded to know their phone passcodes.

The researchers also created a women’s “empowerment” ranking by using survey responses about household decision making, mobility, marital harmony, wearing a veil, natal family contact, financial independence, sexual harassment, domestic violence, latent work, and marriage decision involvement.

More specifically within empowerment, measures of economic engagement, mobility, and community attitudes all showed a significant relation to mobile phone use.

The study also argues that the mobile gender gap can amplify other forms of inequality, such as income, networking, and information access.

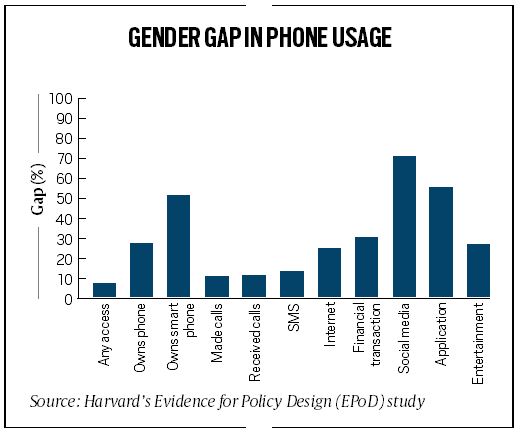

Examining mobile engagement beyond ownership, the study also measured the diversity of mobile activities. As activities grew more complex, the relative gender gap increased. The relative gender gap for making and receiving calls is 15 to 20 per cent, for SMS it is 51 per cent, and for social media use it is above 60 per cent.

Source: The Indian Express

Leave a Reply