By Pooja Salvi & Yoshita Rao

Quintessential life agendas when growing up are pretty much set in stone. Education is the first box to tick off, followed by a job, a few promotions here and there, and eventually marriage and children, before finally succumbing to mortality. However, in the Indian society, these milestones are vastly different for women and men. And here is where our problem begins.

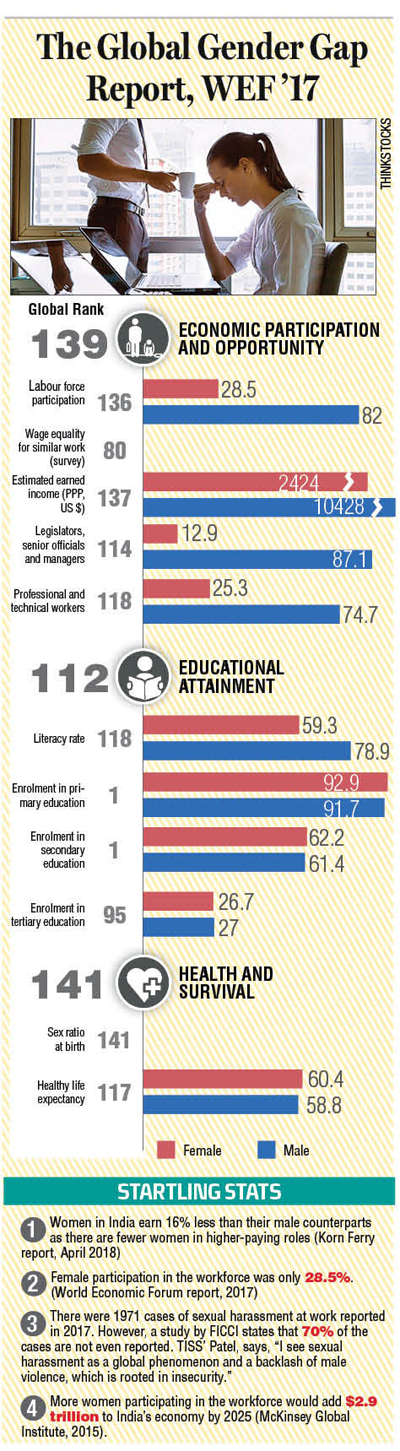

The numbers of female employment rates in India are grim and call for intervention, following a consistent drop of 5% every year during the decade 2005 to 2015, according to a World Bank report titled, Jobless Growth? (April 2018). In 2017, it had pointed to another deplorable statistic in its report Precarious Drop, “…female labour force participation (FLFP) dropped by 1.96 crore women from 2004–05 to 2011–12”.

Headlines stemming from these surveys are often framed in a manner that put the onus on ‘women leaving the workforce’. “Women are not quitting or leaving the workforce, they have been thrown out,” says Vibhuti Patel, Chairperson and Professor at Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS). The predictable societal norms of women being homemakers and leaving the workforce, prioritising their families exists in tandem with the inescapable truth that it is a man’s world. “Women are the last to be hired and the first to be fired,” that Patel asserts is the age old corporate policy.

Informal sector to the rescue

In 1991, Patel recalls, there was massive male unemployment in the informal sector; the reason being, women were and still are cheaper labour. “Tailoring had a lot of women participation, but as sophisticated machinery came up and productivity increased men realised there is money in that and so women were weeded out. Women have to struggle hard to even get jobs as garbage collectors these days,” she adds ruefully. Ragpickers were predominantly women. But on realising monetary benefits in recycling plastic, tin, rags and papers men have now entered scavenging in large numbers.

“In India, the wage gap is dominant because women are concentrated in low income activities, even in a specific sector,” begins Jayati Ghosh, development economist and professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), who penned Never Done and Poorly Paid: Women’s Work in Globalising India in 2009. “The term is occupational segregation. Let’s consider textiles and garment: here, women are doing all the labour work and men are appointed in supervising positions. In teaching, they serve as substitute teachers; in health, they are the Anganwadi Workers and the ASHAs (Accredited Social Health Activist), etc,” she explains. The issue with these government schemes is the refusal to recognise them as workers and instead, tag them ‘volunteers’. On the other hand, ‘women-friendly’ contractual jobs in textile, jute, food processing industries and even clerical jobs at the railways and bus depots often leave them scattering for employment later on.

Among jobs showing an increase in women participation is elderly and child care and domestic work, says Patel. And these being in the informal sector are not always accounted for in employment surveys. “If you go through an agency that offers these (domestic help) jobs, they take away 33% of the salary. So if a maid is offered `18,000, she would end up getting just `12,000 in hand. And so they take up assignments on the basis of informal relations,” she adds.

Care for the increasing ageing population ensues a new crisis. “In the absence of state support or elderly care facilities the burden thus falls on the woman of the house,” Patel laments.

Other hurdles

Women also combat for jobs with artificial intelligence and robotics – earlier employed mostly in data entry and other entry-level profiles, which are now redundant. Male candidates are favoured in tech-savvy jobs where women representation at a senior level is only around 5%. And in the plagued Indian IT sector, where ungendered layoff reach as high as 56,000 (in 2017), women’s chances of landing new jobs, Patel says, are “precarious”. The other tech savvy jobs that await women are from Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) companies, (upto 40% employment as per NASSCOM research). Routine tasks in manufacturing sector, ship wrecking yards, small scale industries in tier II cities and the construction sector where women were first categorised as ‘unfree labour’ and participating in loading, unloading, mixing cement and other such jobs have now been automated.

One would think that making education and skills more accessible to young girls and women could help improve the decrease in FLFP thereby closing the wage gap. However, that is not an entirely foolproof plan of action.

“Making education and skills accessible to more women can only work in a viable/ vibrant economy. But at the moment, the highest unemployment rates we have are for educated women aged 15-24, which is 25% unemployed. Therefore, educating is not going to solve that problem,” JNU’s Ghosh says.

Patriarchal overtones figure widely in this crisis. “After a graduate degree, a boy is expected to get a job and build a career,” says journalist Namita Bhandare, who frequently writes on the gender issues ailing India. “The key point in this expectation is permission – young boys and men don’t need permissions from their families to get out and work. This is a major criterion for women to get a job,” she explains. At the same time, a girl is often asked at job interviews, “When are you getting married?’’ The underlying reason suggests that women in India don’t have careers, they have jobs that they would eventually leave post marriage.

The government condones lack of women participation in the workforce by claiming “…increased incomes of men allows Indian women to withdraw from the labour force, thereby avoiding the stigma of working,” according to the Economic Survey, Financial Year 2017-18 (FY18).

Solutions

So how do we make this work for women? The answer lies in one word: enable. “To enable women to achieve workplace equity, we need resocialisation of young boys and girls to empower them to recognise that they share tasks equally at home and in the workplace. This means bringing all genders to be able to do home tasks that do not, by default, belong to women,” says Suren Abreu, feminist and environmental activist, who also stresses on decisions of married couples to share home and family duties. “From the workplace, wage parity, paternity leave and societal respect for house-husbands are of the essence,” he adds. Speaking of the workplace, JNU’s Ghosh says, “Providing enabling conditions – employment near home, care facilities whether it is creches for children or in other forms, providing flexible working hours, offering more work-from-home opportunities, fostering a safe and secure space for women to work, addressing sexual harassment in the workplace – are valid concerns that need addressing.”

By now, it is established that policies need to be put into place to promote acceptability of female employment along with unrestrained reservation. India’s ‘one woman quota’ in the boardroom of publicly listed companies ensures gender diversity. However this has not been strictly observed as only 12% of all board seats were filled by women in India, a Deloitte 2017 report.“When done at the higher level (management level), reservation could help women change the work culture of an organisation. This means that companies need to retain women who quit the workforce before they reach higher positions (i.e. the mid-level positions) by providing enabling conditions. This comes with more open policies, that come with representation – it’s a circle. You only break it by entering the circle. Therefore, in some areas, reservation makes sense,” she explains.

Inadequate representation of women in this manner leads to them being more men-like. “They no longer think of women as their own – it becomes working women vs them. After all, these women in position who come as scant as they can be, need to survive in an all-male environment,” says Ghosh, a point on which Bhandare heartily agrees.

At the end of the day, adequate representation is the only way out. “We need more women in the workplace to generate progressive policies for women – it is a circle but the only way to get out of it is by entering it one way of the other,” she shrugs. “If there is not enough of us (women) out there, you become a man.”

Source: Daily News & Analysis

Leave a Reply