By Ashok Gulati

India can be competitive in cereals, pulses and oilseeds trade if policymakers invest in creating value chains. Policies that restrict exports should go

The new Commerce and Industry Minister, Suresh Prabhu, has expressed his resolve to expand exports. He has said that increase in agri-exports will not only increase the country’s export basket, but also augment farmers’ incomes and ameliorate farm distress. His objective is laudable and achievable, provided there is a paradigm shift in policy-making from being obsessively consumer-oriented to according greater priority to farmers’ interests. But before elaborating on this, let us compare the trends in agri-trade, both exports and imports, in the period when the UPA was in office (2004-05 to 2013-14) with that of the three-years of the current regime (2013-14 to 2016-17). A close look at these trends and their drivers can help Prabhu and his team identify agri-commodities that can help boost the agri-trade surplus.

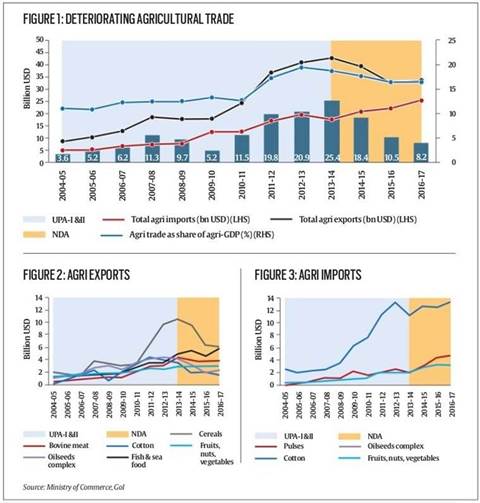

In general, both agri-exports and imports have increased substantially since 2004-05. Agri-trade increased from $14 billion to $59.2 billion between 2004-05 and 2016-17 (Figure 1). As a share of the agri-GDP, the contribution of this trade increased from 11.1 per cent in 2004-05 to 16.7 per cent in 2016-17 after peaking at 19.6 percent in 2012-13, reflecting the increasing integration of Indian agriculture with global markets.

It is interesting to observe that during UPA’s tenure in office, agri-trade surplus surged seven fold, from $3.6 billion in 2004-05 to $25.4 billion in 2013-14. But then fell dramatically by two-thirds after the NDA assumed office, touching $8.2 billion by 2016-17 (Figure 1). The tumbling agri-trade surplus was the result of falling exports and rising imports. Agri-exports, after peaking at $42.9 billion in 2013-14 fell to $33.7 billion in 2016-17, while imports kept rising — from $17.5 billion in 2013-14 to $25.5 billion by 2016-17. Agri-exports suffered primarily due to the significant fall in exports of cereals (especially wheat and maize), cotton, oilseeds and, to some extent, bovine meat (Figure 2). This, in turn, was largely due to a steep fall in global prices and restrictive export policies. Global prices of wheat, maize, soybean, and cotton, for example, fell by 47, 39, 25 and 18 per cent, respectively, during 2013-2016. The FAO food price index fell from 209.8 in 2013 to 161.5 in 2016. Export policies for pulses, oilseeds/edible oils and several vegetables were restrictive. Nevertheless, exports of fish-seafood, and fruits-nuts-vegetables (mainly guavas/mangoes, grapes, cashew nuts, onions) have been growing steadily. They touched $5.8 and $3 billion, respectively, in 2016-17 (Figure 2).

Agricultural imports have been rising since 2004-05. Edible oils ($11.3 billion), pulses ($4.3 billion), and fruits, nuts, vegetables ($3.1 billion) accounted for $18.7 billion of the total agri-imports of $25.4 billion in 2016-17 (Figure 3).

What do these trends mean for policy? First, if India has to promote agri-exports, the country’s policymakers must build global value-chains for some important agri-commodities in which the country has a comparative advantage. Estimates show that India is export competitive in almost 70 per cent of agricultural commodities, non-tradable (that is our prices are between import parity and export parity prices) in about 10-15 per cent commodities, and import competitive in the remaining 15-20 per cent commodities. On the exports front, India is relatively competitive in cereals, especially rice and wheat and maize, and, at times, oilseeds, especially groundnuts and oil meals. The country can also be competitive in groundnut and mustard oil, provided there is an open and stable export policy. India has also been the world’s second largest exporter of cotton.

The country has a great potential to export fish and seafood, bovine meat, and fruits, nuts and vegetables. These are the commodities to focus on in order to stimulate agri-exports. This would require infrastructure and institutional support — connecting export houses directly to farmer producer organisations (FPOs), sidestepping the APMC-regulated mandis, removing stocking limits and trading restrictions.

Stimulating such exports would also require structural reforms in agriculture. When global prices dip suddenly by 25-30 per cent — for example, between 2013-16 — domestic exporters face problems. Export-oriented value-chains may need support in such times. A special package to support value-chains through infrastructural investments (in assaying, grading, packaging and storing facilities), which will also create jobs in rural areas, or assistance in adhering to sanitary and phytosanitary standards would make them more resilient to future price shocks.

Second, India needs to adopt an open, stable and reliable export policy. Abrupt export bans, high minimum export prices to restrict exports, or other quantitative restrictions on pulses, edible oils — even on vegetables and cereals at times — must give way to a policy that does not put any fetters on exports.

Third, on the imports front, India loses out most in the edible oils sector, especially palm and soybean oil. Palm oil is used to adulterate several other oils for the domestic market. Similarly, among pulses, primarily yellow pea is used as an adulterant in besan (chickpea flour). The import policy must, therefore, be designed such that the landed price of palm oil and yellow pea never goes much below the domestic prices of their nearest rivals, say, soybean oil and chickpea, respectively.

Last, liberalisation of factor markets, especially land-lease markets, would also help in building more efficient and reliable export value-chains. Over-regulated land-lease markets have kept landholdings small and forced informal tenancies to flourish rendering them incapable of mobilising large-scale capital. Long land-lease arrangements can facilitate private investments in building export-oriented global value-chains, generating rural non-farm employment and enhancing farmers’ incomes.

It is time for the commerce and industry minister to steer a “farm-to-foreign” strategy, improve agri-trade surpluses by promoting agri-exports, and most importantly create more jobs and bring prosperity to rural areas.

Leave a Reply